VPC Peering is still your friend

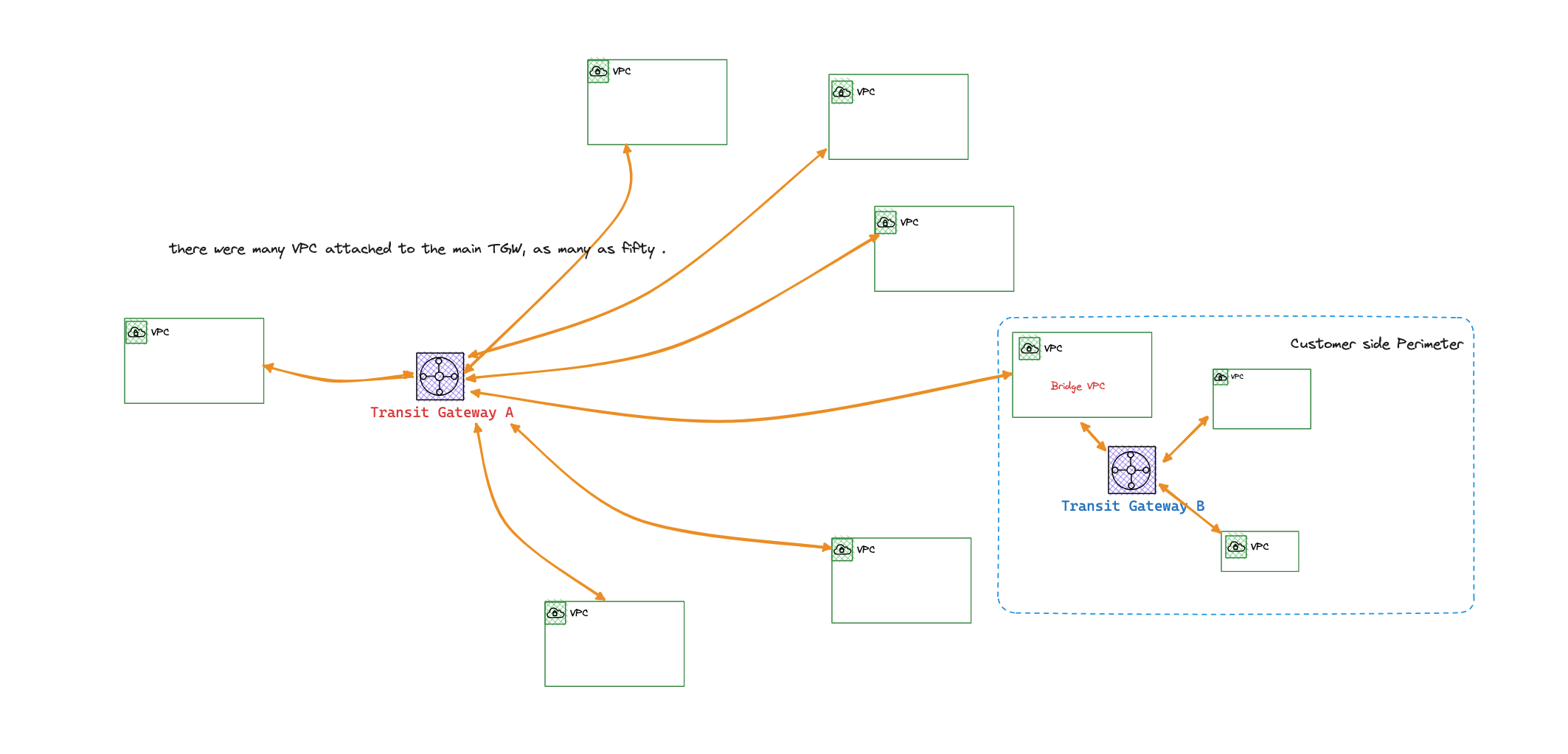

[aws transitgateway vpc-peering I once worked with a customer who had an intriguing networking topology. They had a multi VPC hub and spoke network, with approximately forty VPCs connected to a Transit Gateway (TGW). The purpose of the TGW was to link to a specific VPC that held the control plane, managing the data planes in the other VPCs.

Only the control plane VPC should be able to connect to the data planes in each VPC, while no direct connectivity should exist between data planes. Each data plane VPC is tailored to a specific customer as part of a multi-customer SAAS model. Additionally, each data plane VPC connects to another transit gateway from the customer’s side (we’ll cover this later), creating a maze-like structure.

To illustrate, here’s the architecture diagram:

TGW automatically comes with a default route table, which, by default, serves as the default association and propagation route table. Unfortunately, the customer didn’t opt out of this setting, resulting in any VPCs attached to the TGW gaining access to all other attached VPCs, raising significant security concerns.

This is a major concern as it grants any customer-side VPC unrestricted access to other customer-side VPCs.

Another crucial aspect to consider is that any customer-side data plane VPC could act as a bridge between the main TGW (TGW A) and the customer-side of the TGW (TGW B). While this is possible with a default static route table entry pointing to a data plane VPC attachment from both transit gateways, it’s also just one mistake away from causing potential issues. A robust architectural design should eliminate any room for such mistakes in the future.

The concept of a VPC acting as a bridge between two transit gateways is discussed in detail in this blog post from Giles: AWS Transitive Routing with Transit Gateway. This architecture was sought after for peering TGWs from the same region until recently, when intra-regional peering became supported out of the box.

Intra-Regional TGW Peering via a Bridge VPC

How can we prevent potential mistakes in the future and achieve a fail-proof solution?

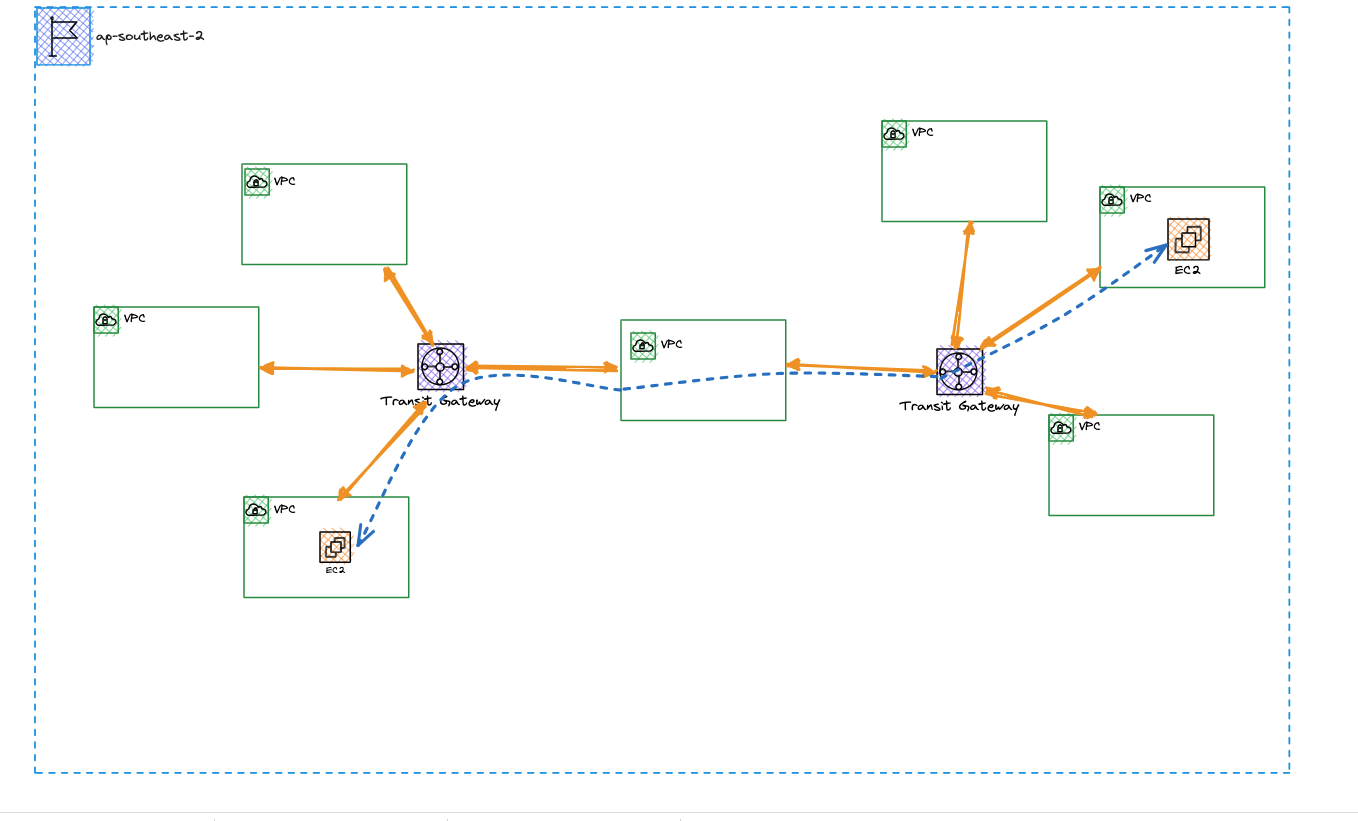

While complete fail-proofing is practically impossible, we can minimize exposure to downsides. The solution lies in a simple answer to this complex problem: VPC peering.

VPC peering is an ideal solution for this problem statement, which includes:

- Centralized control plane communicating bidirectionally with data planes.

- Data planes should not communicate with each other strictly since they belong to different perimeters.

- Introducing a new data plane should easily scale and provide effortless connectivity between both.

- Data plane instances should only accept ingress traffic from the control plane.

Moreover, AWS recently announced that all data transfers over a VPC peering connection within an Availability Zone (AZ) would be free. This is great news for VPC peering users, as TGW can be an expensive alternative for achieving the same end.

Interesting scoop: The aforementioned customer was able to save around 120,000 USD per year by adopting this topology.

The only constraint is that you can have up to 50 peering connections for a VPC, extendable up to 125 connections, allowing you to work with 125 different data plane VPCs (representing different customers in this case). If the company is rapidly scaling and expects to exhaust the limits soon, they can create a new control plane VPC along with as many data plane VPCs. This provides redundancy and partitioning of their control plane at little to no marginal cost.

Transit Gateway costs come in two parts: TGW attachment costs (billed hourly) and data transfer costs, whether between the same AZ or inter AZ. Peering does not carry any hourly attachment costs.

Peering is also ideal for referencing the source security groups from the peered VPC for inbound and outbound security group rules. The peered VPC can be in the same account or from a different account, making it a versatile and powerful solution.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the key takeaway is not to be lured by shiny new services just because they seem exciting and popular. Instead, we should assess solutions based on first principles and consider whether existing solutions can effectively address our needs, as they often prove to be ideal for common problems like these.